One hundred years ago, the sky fell in Dayton. Or to be more precise, rain. A lot of it.

We’re coming up on the anniversary of the worst natural disaster in Ohio’s history, the Great Flood of 1913. By far, the hardest hit community was Dayton, and plenty of people lost their lives.

It could have been a lot worse, which was well-shown in 1913, a wonderful play my family attended last week, performed by Wright State University’s theater department. The play was based on an equally-fantastic narrative nonfiction book, A Time of Terror by Allan W. Eckert (which is, sadly, out of print).

As in the actual event, the play showed some people who died, and many who didn’t, but it was quickly clear that the death toll would have been much higher had it not been for one man who took a great risk: John H. Patterson, the president of NCR (the National Cash Register Company).

John H. Patterson (in derby hat, third from right) surveys the flood (Photo via Dayton Metro Library)

In the play, Patterson is first shown meeting with his executive staff at NCR. He wants to survey the city–in particular, the levees. It had been raining since the weekend, after the ground was already saturated from snowmelt, and Patterson had a bad feeling.

His staff questioned this. Yes, Dayton was prone to flooding, lying in an S-curve where four rivers came together, but the levees had held up just fine for over a decade. Patterson was being alarmist, and was worried over nothing.

But Patterson was a wealthy and powerful individual, so the executives went, and reported back that the river was close, but they were sure it would crest before it reached the top of the levees.

However, the rain showed no sign of abating, and this was not a risk Patterson was willing to take. Dayton was going to be flooded, and it was going to be much, much worse than the last time it had suffered a major flood, he was certain. Fires would break out when gas lines beneath the city ruptured. Hundreds, if not thousands, would be displaced from their homes. Lives would be lost–unless they acted fast.

NCR was located on the south side of town, on high ground. At the time, it was one of the biggest corporate complexes in the world, and boasted its own cafeteria, gym, barber shop, and other amenities for the employees. It also had its own wells and power plant, and was perfectly suited to handle the influx of refugees that were sure to come. So Patterson decreed on the morning of March 23, 1913, that NCR was now the Citizens’ Relief Association until further notice. He ordered employees to procure all the food, blankets, clothing, and medicine they could find. He set the factory workers to stop making cash registers, and to instead use the wood to manufacture hundreds of flat-bottomed boats. He commanded people to work in the kitchens and start baking bread, and making soup, sandwiches and coffee–as much as they could.

While Patterson did a lot for the community–he engineered many benefits such as a night school for employees and well-lit factories–he was also a control freak and a tyrannical boss who fired people seemingly at whim. He eliminated competitors with ruthless precision; in fact, he’d been convicted of antitrust violations just a few weeks before and had been sentenced to spend a year in prison, which he was at the time appealing. When Patterson handed out orders to deal with the flood he expected, people thought he was nuts, but since he controlled their paychecks, they did what he told them to do.

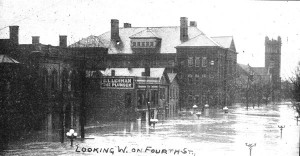

This photo, used on the cover of Time’s Enemy, gives a glimpse of how bad it was – look at the streetlights (Photo via Dayton Metro Library)

An hour later, the first levee broke on the north side of town, and it wasn’t long before refugees began to arrive. Within hours, other levees had broken, and the city was inundated with over 12 feet of water in places. People were trapped in the upper floors of their homes and workplaces, in attics, and on roofs. Workers in the flat-bottomed boats made with mahogany wood intended for cash registers trawled the city for survivors, and brought thousands back to NCR for food, dry clothing, and a place to sleep. In my novel Time’s Enemy, my characters Tony and Charlotte are trapped in a freezing-cold attic, then must flee when fire encroaches. An NCR boat picks them up. Later, Tony helps rescue others.

Depending on which estimates you read, the death toll ranges anywhere from a hundred-sixty-some to over four hundred people. But how much worse would it have been if John H. Patterson hadn’t risked looking like a fool, and risked a great deal of money proactively turning his manufacturing operation into one focused on rescue and relief?

Have you ever seen something coming, but kept quiet for fear of being thought a Chicken Little? Or have you spoken up, and been glad you took the risk? Have you heard about the 1913 flood, and the role played by NCR boss John H. Patterson? I’d love to hear from you!

As a side note, I’m going to be appearing at the Wilmington-Stroop branch of the Dayton Metro Library this Saturday, Feb. 16th, at 10:00 AM to talk about writing romance with readers and fellow authors Macy Beckett/Melissa Landers, Lorie Langdon, Jess Granger/Kristin Bailey, and Stacy McKitrick. There will be coffee and chocolate! If you’re in the area, we’d love to see you there!

Jennette Marie Powell writes stories about ordinary people in ordinary places, who do extraordinary things and learn that those ordinary places are anything but. In her Saturn Society novels, unwilling time travelers do what they must to make things right... and change more than they expect. You can find her books at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Smashwords, Kobo, iTunes, and more.

Jennette Marie Powell writes stories about ordinary people in ordinary places, who do extraordinary things and learn that those ordinary places are anything but. In her Saturn Society novels, unwilling time travelers do what they must to make things right... and change more than they expect. You can find her books at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Smashwords, Kobo, iTunes, and more.